Uniform world standards matter. Partisan and national pride, when blocking the path of progress, stifle efficiencies which in turn eat away at free enterprise’s role as innovators, which in turn can lead to constantly lower costs.

Back in 1986, I was in the midst of another Heidelberg Offset installation- way out west in the pretty little town of Woodinville, Washington State. As every mechanic will tell you, challenges are just part of the job when you’re out of town. Woodinville was no different. No, it wasn’t the surprise of seeing the wall feet from the press receive a massive hole; the next-door occupants were in the broadloom business and to move large rolls of carpet, they used a forklift with a specially mounted steel pole, something similar to a jousting lance. The operator misjudged the distance, and suddenly, the drywall exploded with this pointed pole inches from where I was working.

I had another problem, one rather frequent in a country that still refused to go metric. I needed a few 6mm hex bolts. Such a simple request would have been as easy as running down to a local hardware store if I was anywhere other than the USA. In 1986 America, unless businesses ordered fasteners from a specialist metric supplier, there were none. In bigger printing plants, the maintenance departments usually had assortment kits but generally guarded these as if they were Lady Aster’s jewels. Since the area was new to me, I did the next best thing and went to a Volkswagen dealership, paid a princely sum and solved the problem.

Our museum has just completed a restoration of a Heidelberg stop-cylinder press which was manufactured in 1920. The press is known as the Schnelläufer-Exquisit (fast press) and is hand-fed in a 70 cm sheet size. But if you need any hardware, be in for a surprise. All threads and nut/bolt faces are English Whitworth, not metric. This proved to be a bit of a puzzle since the DIN metric profile, developed in Germany in 1919, came about well before 1920 when the German, French, Swiss, and French established the Système Internationale (SI) in 1898.

1920 Heidelberg Exquisit at HIW Museum

Imagine that! The Germans used British Screws.

In 1841, Joseph Whitworth, the legendary English toolmaker, suggested standardizing threads. Since the invention of the screw, hundreds of profiles have existed and were often made in-house by machine factories. We constantly run across some very odd sizes and pitches in our restoration of pre-1850 machinery. Whitworth chose an angle of 55 degrees and standardized the number of threads per inch, fixed for various diameters. It is considered a credible fact that Frederich Koenig, upon leaving England for Germany in 1817, took with him English tooling and at least one Whitworth lathe. Such was the quality and acceptance of the Whitworth name.

However, Whitworth threads were difficult to cut as they feature a flat milled surface at the top of the thread. In 1864 an American, William Sellers, came up with what would become the American-Unified- Course Series (USS). This thread had a 60-degree angle, similar threads per inch as Whitworth but a sharply pointed thread that was much faster to manufacture. In 1948 Britain, the USA and Canada agreed on a new thread standardization using the Imperial measurement; Unified- National -Standard or UNC. UNC surfaced due to major “tower of babel” bottlenecks during the Second World War. Machinery, armaments, and vehicles manufactured in these three countries would run into trouble when repairs had to be made. For example, a British tank with Whitworth threads breaks down at a Canadian front line, and all the Canadian bolts don’t fit!

Although the sheet size and thickness metric system was prevalent before 1919 Europe, changing tooling and specifications to suit the new system was incredibly expensive. Whitworth's specifications had spread throughout Europe, especially Germany, which was becoming the juggernaut of machine building. Tooling cost money that few companies, including Heidelberg, had available just after the First World War. Every printing press we have worked on, some built as late as 1930, used imperial hardware, including Koenig & Bauer, Johannisberg, Mailänder, and Planeta. These printing presses used British threads, but our museum also has a 1927 Heidelberg Platen, and we do know that between 1920 and 1926, Heidelberg did adapt to the metric system.

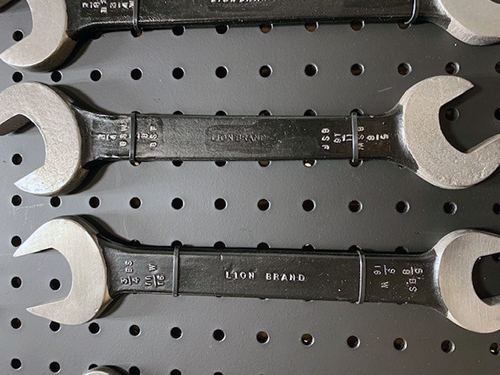

Top: German Whitworth wrenches

Bottom: British Whitworth wrenches

Why are Toolboxes so heavy?

To mask the fact that Europe was still maintaining an imperial unit for hex bolt and nut faces, odd size wrenches appeared with a metric identification and sometimes with applicable fractions to accommodate the Whitworth size. Metric hex bolt face sizes 14, 16, 18, 20, and 25 millimetres (now obsolete) were conversions from Whitworth. For example, early German wrenches would sometimes be stamped 25mm and 9/16”. If by chance a fine thread was used (BSF), that same bolt would have a completely different wrench marked 5/8”: Whitworth, for some reason, altered the faces from coarse (BSW) to fine (BSF). To make matters even worse, various European countries, including the USA, developed their head sizes which meant mechanics needed more tools to lug around.

In Japan, the situation wasn’t much different. A 1928 Komori press in our Museum is manufactured to Imperial measurements, and all the fasteners are Whitworth. When Germany and its neighbours, tired of the heavy English threads and bolt faces, eliminated the irritant and went completely metric. Metric bolts maintained the American 60-degree angle but altered the thread pattern towards a slightly finer pitch.

Unusual thread patterns only added to the grief in the USA. Smyth bindery equipment didn’t use typical threads, and simple things like screws, bolts, and nuts were all listed in their parts catalogue as unsuspecting mechanics would soon find out they were non-stock at most suppliers. I spent hours re-threading a hole to accept a standard thread for a Smyth case maker: frustrating and wasteful but potentially profitable for the manufacturer.

Ultimately, if a single standard defines every bolt and bearing, “billions” of dollars could be saved along with endless hours of searching. There would be no need for multiple sets of taps and dies, drawers of wrenches, Allen keys and eye-watering SKUs of dissimilar stock.

DIN’s other wide-reaching standards also had a profound effect on virtually everything else. Paint colour is a good example. The RAL standard also came with a number. In the USA, they still used catchword monikers such as “Battleship Grey” and The Germans: RAL7003. Every shop in Germany made that colour the same.

Sorry…. We can’t supply that!

Non-standard wasn’t isolated to hardware but ball bearings as well. General Motors once owned New Departure (now Hyatt-New Departure). During World War Two, ND manufactured 287 million bearings for the war effort. They went into everything from aircraft to tanks. As the war ended, New Departure came up with a novel annuity revenue stream. Various odd dimensions were designed into some New Departure bearings. If a manufacturer specified them when it came time for a replacement, the customer could only purchase it through the same manufacturer as bearing suppliers couldn’t sell it. Our British friends are quite familiar with this money-maker as they had various firms, such as Hoffmann, knocking off unusual products only they could supply. Just as with a simple concept of standardizing a bolt, history shows what a waste in capital differentiation can mean.

Today access to metric fasteners in North America has dramatically improved. Hardware stores usually supply the most common items. Whitworth is still alive, primarily centred in the UK but specified for various products such as cameras. The threads make spinning on a nut much easier than metric or UNC. The Marine and shipping industry often specifies Whitworth. Japanese metal shipping crates use Whitworth ½-12 hex bolts for some unexplainable reason. BSPT (British Standard Pipe Thread-Tapered) is also used worldwide, although Europe generally accepted the American NPT (National- Pipe Thread). Probably many of you struggled to match electrical connectors with European hardware. That’s because of the PG standard created within the German DIN system. Panzergewinde is the name of these tapered threads and requires yet another set of taps that few in North America even know about.

Heidelberg Exquisit at HIW Museum

Ultimately, if a single standard defines every bolt and bearing, “billions” of dollars could be saved along with endless hours of searching. There would be no need for multiple sets of taps and dies, drawers of wrenches, Allen keys and eye-watering SKUs of dissimilar stock. Ponder the benefits for paper and even lumber specifications: massive savings. Canada officially adopted the Metric system in 1970, but most Canadians my age weigh themselves in pounds and measure their height in feet and inches. Thousands of my fellow Print industry mechanics have suffered from non-standardization for decades; perhaps our Governments will finally do something about it.

contact the author